Every country has its own culture and traditions, and the food is an inseparable part of it. During my studies of cultural history, some of my research involved examining Medieval and Early Modern cookery books from Europe.

I can tell you one thing: there wasn’t a country I researched that didn’t feel proud of some dishes that a modern person wouldn’t call controversial. Starting from a Christmas carp in Poland, through kangaroo steaks in Australia, fermented shark in Iceland, live octopus in Korea, balut in the Philippines, the list goes on.

Since I started traveling to foreign places, I always tried to taste traditional foods wherever I went. When I was younger, eating something exotic and local in a foreign country was surely something I wanted to do on my travels.

But, as the internet wasn’t as widely available to everyone as it is now, it wasn’t so easy to simply google something to find the history of it and how the dish is made.

However, these days quite often, I restrain myself from sharing my experiences online as I see others getting attacked for doing something they thought would be a cultural immersion. How can a traveler know which dish is ethical to try and which isn’t?

This topic that isn’t as simple as it may seem.

Should You Eat “Controversial” Local Food When You Travel?

To be, or not to be, vegetarian abroad

I actually used to be vegetarian. When I was a kid in Poland, where red meat is an inseparable part of country’s culture and daily life, becoming vegetarian was surprisingly easy. Even considering the fact that I’m slightly fruit intolerant and can’t eat too many raw veggies. There was always plenty of choice of vegetarian food in every supermarket, and since the beginning of new millennium, vegetarian restaurants have become more and more common.

However, as you may have noticed in some of my videos or behind the scenes Insta-Stories, I’m not vegetarian anymore. It’s when I traveled, however, that things became more difficult. I was forced to question whether refusing to eat something the locals love so much is really the right and polite thing to do.

Food is a way to build bridges, to accept hospitality and form friendships beyond any language barrier.

If you’re traveling to all-inclusive resorts or popular touristy places, finding vegetarian or even vegan food isn’t a big issue. These days people seem to be obsessed with healthy acai bowls and raw vegan food, especially since it’s all very Instagrammable. However, in certain places, being vegetarian wasn’t east at all. I remember being an intern in Mendoza in Argentina, a place nestled between a desert and mountains, a place known for its meat.

Mendozinos definitely didn’t understand my desire not to eat meat, which led to many awkward situations, such as them bringing me a chicken that in their definition wasn’t meat, or serving me a spinach and bacon lasagne, explaining that they thought it’s vegetarian since the majority of it was spinach. But hey, this wasn’t a big problem for me.

Nevertheless, the first big cultural shock I remember was my time volunteering in Zimbabwe. I spent time with locals who lived in cramped clay houses with basic food rations. They ate what someone in the village caught that day and shared everything they had with themselves and their guests. They were very excited to host me, and quickly offered some bread with jam, cabbage, pieces of meat (I believe it was wildebeest or warthog) and pap – local corn porridge.

They put their hearts into giving me their part of the food. All I could do was eat it and really appreciate and enjoy the time we got to spend together. Imagine how awkward would it look like if I said: I don’t eat meat, I eat tofu. Or that Pumbas (warthogs), one of a few things they have, are too cute to eat.

I didn’t want to be culturally superior by having my own food preferences. After all, I wasn’t allergic to meat like some people are to gluten or lactose. It was just my choice, one of those ‘white people food choices’. It’s a great luxury for the privileged nations to be able to turn down animal products just because they feel like it.

Was I really going to go to some small remote foreign place where they eat what they can have and refuse what I’m served? Should I ask for ‘a salad without a dressing, meat, and a toast but with no butter and avocado on top’? It’s a rhetorical question of course.

***

Refusing to eat meat products abroad in just a tip of the iceberg in an ongoing debate on eating local food abroad. It’s the meat that’s usually controversial. Not all traditional delicacies are considered ethical by other nations. More and more cautious travelers debate whether they should try some things to be polite, or refuse them because of their own beliefs?

Let me ask this fundamental question first: What does ethical eating mean to you?

In most cases, people think that food they grew up on is acceptable.

Local women making bread in Iran

The issue of exotic meats

When I recently traveled to Norway, few of my followers sent me messages saying that they’re horrified by the fact that I ate a reindeer. I asked them whether they were vegetarian or vegan. I wish those who were indeed wouldn’t act like a vegan police telling everyone what to eat and what not to eat, but to my surprise, the majority of the ‘horrified people’ were meat eaters.

Reindeer just seemed too weird and cute to them, but they happily ate pork, beef or chicken at homes. Apparently, a piglet wasn’t cute enough.

This is where things got tricky, as when in Norway I also saw jackets made of reindeer fur and seats made of reindeer skin. Something that in the US or UK could result in being ostracized by your friends for life. But there’s a reasoning behind skinning reindeer that I actually wholeheartedly support.

In Sami’s (Sami are indigenous Arctic people) folklore there’s a story about how the Sami struck a deal with the reindeer out of respect to them. They promised to look after them well, feed them, and make them happy. In return, reindeer would offer themselves as food in exchange for a promise to make use of every part of them and not just slaughter them when it’s not needed and make it go to waste. Guts and other parts that humans don’t eat are given to dogs.

To me, this made way whole a lot of more sense than breeding and slaughtering animals in most meat factories in the US. Samis aren’t producing it to export internationally on a mass scale but just didn’t want to unnecessary waste the animal after slaughtering it. This, on top of the humane treatment of their reindeer, and the commitment of the people caring for them.

It can’t even be compared with beef and pork ‘farms’ (as I can’t even call them true farms) that I accidentally drove pass in California, with animals being crammed in small spaces, some covered in their feces, where, in the end, a lot of even good meat goes to waste. How’s this not more horrifying and unethical than eating a well-cared for reindeer?

***

Different cultures have different values. If you insist yours is correct, I think that becomes problematic.

You need to understand that much weird local food isn’t weird to them. How do you feel about the consumption of beef? It seems normal enough. If you were raised in India, it wouldn’t be. They would be petrified at the idea of you eating your beloved burger as cows are sacred. How about pork? Try asking someone from Israel and they’d tell you that pigs are unclean to eat.

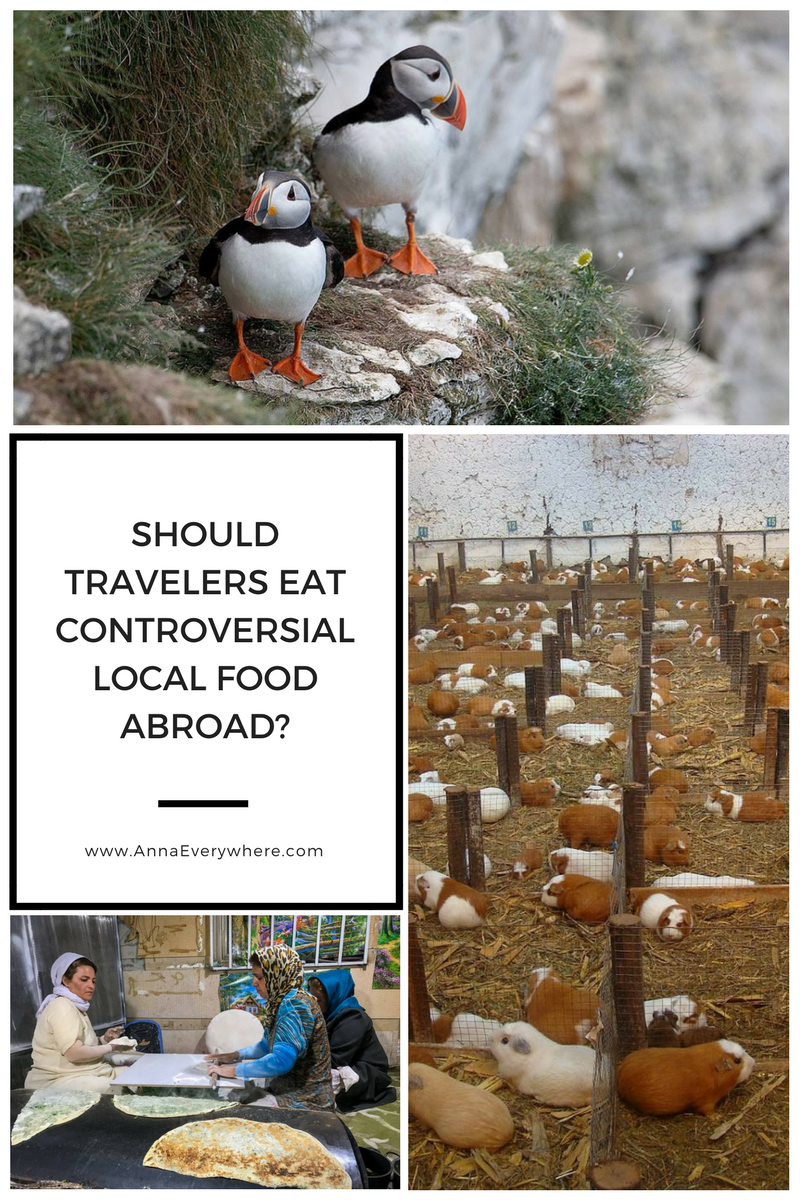

Now, what about eating a camel, reindeer, alpaca, warthog, guinea pigs, puffins or horse…?

Are Indians staging demonstrations against beef at In-N-Out or other burger places that serve it in the same way an American protesters attempt to shut down the dog festival in China? I’m not saying I support the eating of dog meat, but most reasonings behind the slogans don’t make sense. Is it because dogs are smart and we keep them as pets?

We treat dogs differently than we treat pigs. Although, pigs are way smarter than dogs and have a mentality of a 3-year old kid. Pigs also dream, see in color, love social cuddles, and are more hygienic than dogs. But we’re used to pigs being bred for food, so what’s wrong with eating them?

In many Asian countries, we could pose the same question about dogs. I bet you maybe only 30% of the people protesting the dog eating would sign the same petition against slaughtering pigs and would rather enjoy their bacon for breakfast. But I’ll stop this paragraph now before you accuse me of trying to convince you to quit bacon.

***

This leads to even a more important question…

Does it seem all right to you to be going to another country telling them what to do with their culture as a visitor?

This is why we need to ask a question: where the fine line? What do you do, as a traveler do when you’re served food outside of the comfort zone? Do you refuse it politely, or do you give a speech on what’s wrong with it, or do you just eat it accepting people’s ways?

Guinea Pig farm in Ecuador. The roasted guinea pig is a traditional dish in South America.

Many local foods became traditional by accident.

How some foods ended up popular in some cultures? If you studied some history, you know that back in the days, kings and high society demanded extravaganza in food. Sourcing from faraway places was thought to be the ultimate in elite eating. Just like nowadays we love colorful unicorn cafes serving adorable rainbow food or colorful lattes, new flavors were something people were looking for.

In England for instance, Queen Elizabeth brought potatoes and chocolate to Europe, Victorian times brought mangos and caviar, not caring that the beluga sturgeons knocked on their heads and gutted. No one cared about lobsters being boiled alive either (even today the only country that banned it is Switzerland).

Following, the early 90s were the times when people cherishing foie gras from tormented barnyard fowls and ducks. Our only debate as humans was a discussion being whether goose or duck produced the superior product. Some foods stayed present in our society up until now and are considered normal. I don’t see many protesters against it.

I recently read an article which stated that at some point the Victorian society tried to acclimatize exotic wildlife in Europe for the purposes of eating it. Elephant soup, kangaroo steak, antelope, fried camel. It turned out that there was no interest in eating a hippo or elephant, as supposedly they didn’t taste good, and on top of everything the efforts of acclimatization and farming them failed miserably. Thankfully. Instead, for a while, people enjoyed the rat pudding.

But it didn’t just happen in Europe. In 1910 in the US there was a shortage of meat. The price of beef skyrocketed due to an incoming flood of immigration, so someone had to think of another solution. This is when the representative of Louisiana proposed a Hippo Bill and America almost got into farming them. Can you imagine eating hippos for dinner? Maybe it would have been normal to you, just as it is eating a cow?

Can you imagine them for dinner?

It’s not easy to change some traditions overnight

On a final note, someone recently asked me about Polish Christmas. It’s been almost 15 years since I spent a proper Christmas there, but I explained that one of the traditional dishes is a jellied or fried carp that you buy alive at the supermarket.

I remembered it swimming in a bathtub for about a week until someone in the family finally killed it on the 24th of December and prepared it. I had a mini-tradition with my dad even had a tradition of buying two carps and letting one go to the park where other carps lived.

The minute I said that it came to me that it’s a terrifying tradition. Who in the right mind would pack a fish into a plastic bag and bring home, then make it swim in a bathtub (if your house had any, some used a big barrel) in circles and then kill it? What’s even worse is that I briefly remembered one year my own grandma leaving the poor carp in a bag until her neighbor came over a few hours later, because she didn’t want to kill him herself.

Final carp product.

The tradition started in post-communist Poland where there was barely anything in shops and fridges weren’t available to everyone. It made sense that no one wanted to prepared the fish before the actual day of consumption. With only vinegar in the fridge, scoring a carp was a symbol of success as sometimes you had to stand in line for up to 5 hours and still get nothing.

Despite Poland now is a much wealthier country, where everyone has a fridge and more, the lowly carp continues to dominate the holiday table. About 7.5m live carp are sold for the holidays every year.

As an adult, I started researching this issue. I suspected correctly, the carp traditional was indeed under fire by animal rights groups. Even celebrity chefs are campaigning against it, but not all people agreed. The older generation doesn’t agree with buying fillets of a carp carcass. Some people I spoke to found it unacceptable that they can’t continue the tradition of descaling a carp (already dead one thankfully) in order to keep the scales in your wallet for good luck until the next year.

The Problem of Iceland

Iceland is without a doubt one of the most popular travel destinations and experiencing a tourism boom. It’s also one of the countries with way too many controversial dishes. Even Anthony Bourdain got slammed online by eating some local food there.

Most believe the Icelandic food includes a minke whale, fermented shark, lamb’s head, horse, and even puffins. For centuries, Icelanders had to eat what they caught and do whatever they could with it. They smoked, dried and pickled their food to preserve it through the harsh winters.

Puffins

There are regular protests against eating most of these things, the whale in particular. But when I asked my Icelandic friend to get me some typical dishes she suggested the hot dogs, licorice candy, and the Christmas mutton smoked in lamb’s dung – yes, the poop!

When I asked her about these controversial dishes, she defended it by saying that it’s their tradition and they have laws regulating everything. She told me that while minke whale has never been considered endangered and now they have limits placed on how many whales can be caught each year (which isn’t supposedly true…), but more importantly she said that regular people eat it maybe only once or twice a year, if even.

The question that arises here is where do all this whale meat go if locals don’t eat it? Tourists eat it. It’s tourism that drives this industry, which ultimately, isn’t a good thing. But regardless of the issue what does this do to the whale population, the food stops becoming traditional as well if locals aren’t its prime consumers. Keep this in mind next time you visit Iceland and decide for yourself.

[su_row class=””] [su_column size=”1/2″ center=”no” class=””]

[/su_column][su_column size=”1/2″ center=”no” class=””]

[/su_column] [/su_row]

Food is an inseparable part of travel, and part of it is accepting the saying that in other countries: it’s not wrong, but different. At least no cultures cultivate the tradition of mellified man anymore (more about it here, if you have a sensitive stomach only read it if you haven’t eaten for a while). The issue is way more complex than classifying something as right or wrong.

What do you think? Do you think we can find a way to sort through a growing array of ethical beliefs when abroad?

Mimi

Monday 1st of June 2020

Some real food for thought!

Dawn

Monday 1st of April 2019

Wonderful post! I appreciate your honesty and insight, and couldn't agree more with your points. XOXO

Aprajita Kohli

Wednesday 20th of March 2019

Anna, your post subjects are really an inspiration to read. Thanks for writing on such interesting topics.

Nir

Monday 18th of March 2019

Surely you can visit mc in every country (so my travel friends do). But this way you will never taste traditional dishes

Annmercy Wawira

Friday 8th of June 2018

wooow. I love reading your articles. Thanks for sharing